A guilty confession: as much as one tries to be absolutely impartial until the final curtain falls, I didn’t go into Soul Samaurai expecting to like it very much. I’m not the kind of girl who thinks that theatre should be more like movies, nor do I have any particular fondness for Kill Bill or blaxploitation. As I’ve admitted here before, I hate fun, and this show looked suspiciously like it was trying to be just that. And the first ten minutes of the show confirmed my every fear: the cell-phone announcement (a pre-filmed racial smackdown between action figures of G.I. Joe ninjas Snake Eyes and Storm Shadow) was irritating, and a few early scenes seemed like by-the-book trash-talking fight sequences.

But I wouldn’t be admitting to any part of this story if it didn’t have a happy ending. To my surprise, by the end of the show I was completely taken in, to the point where I had to work to cover my childlike glee with a veneer of professionalism. In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to find two more frenetic and engaging hours of entertainment—live or otherwise—in this city.

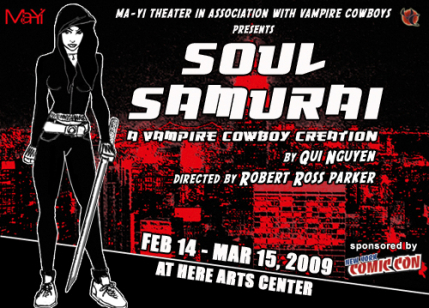

But before we get into that…. As our heroine Dewdrop (Maureen Sebastian) puts it right before launching into an exposition dump, “Let’s do a bit of a rewind first, shall we?” Soul Samurai is the joint work of Ma-Yi Theater Company, which is devoted to “develop[ing] new plays and performance works that essay Asian American experiences,” and Vampire Cowboys Theatre Company, which tends “towards the creation and production of new works of theatre based in stage combat, dark comedy [and] a comic book aesthetic.” While both of these goals are fulfilled to some extent, VCT’s is certainly the more prominent of the two, especially their allegiance to comic books: every fight scene seems to have at least one freeze-frame that obviously would have been that issue’s splash page. But Robert Ross Parker’s direction seems to owe more to the silver screen, from the general—including the aforementioned nods to blaxploitation films, as well as a strong engagement with kung-fu movies, hip-hop music, and pulpy science fiction action flicks—to the specific—such as montages, filmed interstitial sequences projected on wall panels, fight scenes with Matrix-style slo-mo sections, and the lack of an intermission (though, really: even if movies are habitually longer than two hours, if your play is that long and offers a good opportunity for a break, take it).

It was that promise of science fiction action that brought Tor.com to the show, and it certainly delivers in spades. The story is set in New York City in a post-World War 3 near-term future, resulting in a post-apocalyptic New NYC where each borough is run by a shogun warlord. Boss 2K (Sheldon Best), who runs Brooklyn, thinks he’s a normal guy until he discovers that he comes from the Mamuwalde family and shares some of the bloodline’s innate powers (I only picked up on the sly reference after the fact). Before you know it, 2K presides over hordes of vampire-like Long Tooths, which he uses to maintain his supremacy over the borough. And maintain it he does, until he incidentally rubs out Dewdrop’s girl Sally December (Bonnie Sherman), destroying a love so strong that Dewdrop is willing to spend five years learning to be a badass samurai to get her revenge.

However, it’s not the SFnal elements that made this show for me, but the incredibly endearing, incredibly versatile, and incredibly tiny cast: five talented actors who manage to create over twenty speaking characters and countless silent ones (well-differentiated by Sarah Laux and Jessica Wegener’s evocative costumes) between them. It’s impossible not to like Maureen Sebastian’s Dewdrop, a shrinking violet who falls deeply enough for the intensely feisty Sally that it eventually brings about a complete character change. Dewdrop and Sally get across enough of the depth of their relationship in a few brief scenes that you can’t help rooting for it. But it’s Dewdrop’s hapless B-boy sidekick Cert (Paco Tolson) who consistently steals the show. He doesn’t get the girl, but he does get most of the best lines, and delivers them with a perfect blend of feigned toughness and dorky sincerity.

Of course, writer Qui Nguyen’s script gets a lot of credit here as well. While most of the forward momentum of the plot is carried out in cannily-scripted AAVE/jive, you can tell Nguyen’s expertise goes far beyond this style from the varied tone of the flashbacks and interstitial segments. These interludes ricochet from the childlike air of an adult puppet show, to a snarky fairy-tale take on the love lives of fruit, to the lilting and slightly oblique “Tale of Marcus Moon.” Regardless of the dialogue style, surprising and funny lines kept appearing at a regular clip. But, like the rest of the hardworking ensemble and creative team, writing a good script wasn’t enough for Nguyen. He also turns out masterful work as the play’s fight director, which makes him one of the more unusual double-threats in the New York theatre scene. Given this multitasking, it’s not surprising that the stage combat—which many productions treat as an afterthought—is a matter of beauty and primacy here. Only the final battle, so epic that the challenge to the actors is perceptible, flags in the slightest; but it will surely become more fluid as the show’s run continues.

After I got into the rhythm of Soul Samurai, it became harder to remember how we got off on the wrong foot to begin with. Eventually, though, I realized that a lot of my misgivings arose from the racial minefield the show chooses to play on. The first few scenes are particularly rife with the sort of blaxploitation-era stereotypes that have always made me a bit uncomfortable, and Dewdrop’s sensei Master Leroy (also played by Sheldon Best) is basically a black Mr. Miyagi, just as endearing—and just as much of a caricature—as he was in the 80s. I can’t help invoking a world of white privilege when I say this, but there’s a reason blaxploitation only exists as parody these days, and making a raft of stereotypes look even more ridiculous by populating it with actors of other races doesn’t exactly help dispel these myths. In the end, I’m not sure how we’re supposed to benefit from retreading these paths if we don’t examine or challenge them. Ma-Yi and VCT’s general intent is so obviously good that I doubt a few off moments could do any real harm, but I’m not sure that the “We’re all liberals here!” clause is the get-out-of-jail-free card they seem to think it is.

Aside from these social gaffes, the show has a few significant plot holes, some paradoxical timing on the character creation front, and a vaguely dissatisfying ending, but those flaws didn’t actually bother me much—they’re certainly nothing worse than you’d expect from a standard Hollywood movie. And at least Soul has the courtesy to distract us from them with funny interludes and flashy scene changes.

On the whole, these are small complaints for a show that leaves you as giddy as this one does, and if a grinch like me can enjoy it, you can too. If you’re in or near New York, if you like comic books, if you like violence, if you like gorgeous and brave lesbian samurais, or if you’re willing to spend less than the cost of two movies for a night of live entertainment, Soul Samurai ought to be in your game plan.

Pictured: Maureen Sebastian and Bonnie Sherman. Image by Jim Baldassare for Vampire Cowboys Theatre.

Soul Samurai is playing at the HERE Arts Center (145 Sixth Avenue, New York, NY) through March 15, 2009. Tickets are $25 or $20 for students and seniors and can be purchased from here.org.